You may remember last month we talked about THE founding document of the United States, the Declaration of Independence. The focus of the Declaration was two-fold, first to establish the philosophy behind government. Using ideas from Enlightenment philosophers John Locke, Thomas Hobbs, and JJ Rosseau, and others, the Declaration shows that government gets its power from the consent of the governed. When the governed take away their consent, the government needs to be changed. Second, the Declaration lists the reasons why King George III is a tyrant and unworthy of their continued support. I pointed out that the Declaration of Independence used the words united States with the capital on the States not the word united. When Congress declared its independence, it acted on behalf of a confederation of thirteen independent countries. This wasn’t by mistake; the colonies were rebelling against a strong monarchy. The last thing they wanted to do was replace it with a strong federal government. Each new state felt they were closest to their people and knew how to meet their needs. Any strong central government trying to make laws for thirteen geographically and economically different states would become as tyrannical as the one they were trying to throw off.

It took a little time for the consequences of the quickly established government to come to fruition. Each colony was founded with a unique charter from the king. They relished both their uniqueness and ability to control and direct their own destiny as colonies and then as States. By joining in a military confederation, they fought the Revolutionary War with a combination of Congressional troops, state militia, and minute men volunteers. War debt accumulated by each type of government. Repaying that debt became one of the growing issues faced by the newly freed colonies. As the years went by various congressmen began to realize the federal government was too weak.

It wasn’t like anyone had an example that could be duplicated. An original answer was needed, one that was unique to their situation and geography.

As debts ballooned and unpaid soldiers sold the chits/promissory notes for their service during the Revolution to financiers and speculators who paid pennies on the dollar, the United States became a fractious confederation that was quickly becoming ungovernable as a unit. While in Congress, James Monroe expressed his concern about problems with different currencies. Increasingly states resorted to script, or paper currency. Each state had their own with varying degrees of ability to back the money up with specie (gold or silver). In addition to the value of the various currencies, differing currencies made interstate commerce difficult. Imagine the exchange rate for 13 different states. A similar issue existed for weights and measures.

The Articles allowed each state to levy its own tariffs and tolls. This restrained trade and generated bad feelings. Some states shared navigable rivers: the Potomac flowed between Virginia and Maryland, and the Susquehanna from Pennsylvania through Maryland. Who would collect the tolls, and who would pay for the maintenance? Other states had no ports-cargo bound for New Jersey came through Philadelphia and New York-which left them at the mercy of their neighbors.

To some, it was a matter of time before European powers would come in and pit one State against the other. In a letter Jefferson wrote to Edmund Randolf he wrote, “the states will go to war with each other in defiance of Congress. One will call in France to her assistance, another Great Britain, and so we will have all of Europe at our doors.” While in the Virginia Legislature Madison sponsored a resolution to give the federal government permission to regulate commerce for 25 years. He was already considering the shortcomings of a weak federal government. Here are a few of the more obvious problems with a weak federal government.

One event that helped trigger the growing realization for a stronger federal government was Shay’s Rebellion.

The problem with debt and the value of the wages not paid to soldiers came to the forefront in September 1786. Henry Lee wrote to Washington that the restlessness was “not confined to one state or to one part of a state,” but rather affected “the whole.”1 Washington wrote to friends such as David Humphreys and Henry Knox, conveying his alarm at the turn of events in the states, and in response received reports that confirmed his fears.

Protests in western Massachusetts grew more tumultuous in August 1786 after the convening of the state legislature failed to address any of the numerous petitions it had received concerning debt relief. Daniel Shays quickly rose among the ranks of the dissidents, having participated in the protest at Northampton courthouse in late August. Shays led organized protests at county court hearings, effectively blocking the work of debt collectors. By December 1786, the conflict between eastern Massachusetts creditors and western rural farmers escalated. Massachusetts Governor James Bowdoin mobilized a force of 1,200 militiamen to counter Shays. The army was led by former Continental Army General Benjamin Lincoln and funded by private merchants.

The rebellion called into serious question the state of the country’s finances and the viability of the weak national government under the Articles of Confederation. Shays’ Rebellion accelerated calls to reform the Articles, eventually resulting in the Philadelphia Convention of 1787.

A meeting was scheduled in Annapolis for the purpose to consider “measures…to cement the union of the states.” They didn’t get a quorum leading to another meeting to be held in Philadelphia. A few members of the Annapolis Convention decided to come to Philadelphia prepared. Madison got to work on a draft document that would become the template for discussion at the second conference, now known as the Constitutional Convention. He wanted a strong federal government, one that represented the people instead of the States.

While in Paris as Ambassador, Jefferson sent Madison a trunk with 200 books about the subjects of government and history. Madison researched ancient democracies, both representative and direct. He looked at contemporary examples. He read a lot of history. He put his thoughts together in an Essay titled “Ancient and Modern Confederacies.” He followed this up with another essay titled “Vices of the Political System of the United States.” Next, he went to work giving his ideas some structure. Looking at the news and his own observation Madison saw the states acted against each other and acted on their own. The states could not act together on matters of “common interest”. Congress’s laws were dead letters because Congress had no power to enforce them. When the moment came, he wanted to have a plan, a starting place to guide the conversation. His plan not only needed to address these glaring issues, but it also needed to not be England, and it needed to not be a monarchy. Those Enlightenment ideas we looked at last month were forefront in his mind. Division of power was the only way to prevent tyranny. He thought the country needed a strong executive.

Madison wrote to his friend and governor of Virginia, “Our situation is becoming every day more and more critical. No money comes into the federal treasure. No respect is paid to the federal authority, and people of reflection unanimously agree that the existing confederacy is tottering to its foundation.” Madison feared that a monarch might rise up out of the ashes of the confederacy.

In the summer of 1783 Jefferson wrote to William Sterne Randall, he proposed a constitution that prefigured the document of republics in Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America as well as the Confederated States of America and the 1787 revision of the Constitution.” The powers of government”, he wrote, “shall be divided into three distinct departments, each of them confided to a separate body…those which are legislative to one, those which are judiciary to another, and those which are executive to another. “

In our last session I talked about Enlightenment ideas expressed by. Locke, Hobbs, and Montesquieu, specifically the ideas that government gets its power from the consent of the governed.

People who live in a state of nature are free to do whatever they please. But to secure liberty and safety, they give up some of their freedom to live in society.

Any government where the person(s) who write the laws also carry out the laws results in tyranny. A division of powers designed to check the ones who write the laws from those who carry them out with a third body to determine if the laws are congruent with the principles of government is an effective way to limit tyranny.

Even though the Confederation was too weak to meet the needs of the growing country, the founders didn’t want a king or anything that looked like a hereditary monarch. If they were going to have an executive, he would be prevented from being tyrannical.

We know the two major compromises, one to honor states regardless of geographic size of population and one to determine the number of representatives in the House.

While the basic structure of the government is laid out in the first three articles of the Constitution, the members of the Philadelphia Convention knew they had formed a different government than they had originally established. They also knew, before they left the room, what the major talking points would be from the opposition. With these things in mind, Article VI makes the supremacy of the new Constitution clear. Today this is not as controversial as it likely was when it was written. Americans considered themselves to be Virginians and New Yorkers before Americans. Even as late as the Civil War, Robert E. Lee turned down Lincoln’s offer to head the Union Army because he felt he needed to be faithful to his country (Virginia.) Note the object of the oath of office. It is to the Constitution, not a monarch or person. A closer look reveals the oath to the federal constitution is not limited to federal offices but extends to state office holders.

I find it interesting that they specifically prohibited a religions test. To the modern reader the statement may have a broader meaning. While Maryland was formed as catholic colony and Pennsylvania a haven for Quakers, Religious diversity didn’t expand very far beyond Protestantism. Under the category religion, the modern reader will likely include Islam, Hinduism, Taoism, Buddhism, and other world religions, but the founders likely didn’t consider the statement so broad. What they were concerned about was the consequences of the English Reformation.

As a quick overview, the Reformation in England wasn’t a result of doctrinal issues. It came about because Henry VIII wanted to divorce Catherine of Aragon. The Pope wouldn’t allow it, so England broke away, using Luther’s Reformation as an tool for the monarch’s will. The English or Anglican Church was supported by a government tax and its head (the English Pope if you will) was the monarch. Because of these actions, only the Church of England was supported by the government. The members of Congress didn’t want a sponsored church of any kind. It was up to the various churches to support themselves in society. By rejecting a religious litmus test as a condition of public service the founders created a secular government that could include people of faith. As I understyand it their aim was neutrality. Many of the founders were of the protestant faith and that faith was a critical aspect of their life. What they wanted was a government independent of any religious structure or ties with any specific church.

Since unanimity was nearly impossible under the Confederation government, the document created in Philadelphia had its own rules for adoption. As you imagine, Congress wasn’t going to vote themselves and their institution out of office (some things never change.) To help the citizenry understand the difference between the Confederation government and the proposed federal government, Gouverneur Morris wrote a preamble. It set the stage for the republic while it rested on Enlightenment philosophy. If the Articles of Confederation had a preamble it would have been, “We the States…”

Even though nine states were needed to become effective, if Virginia and New York didn’t ratify the new government would not have come into existence.

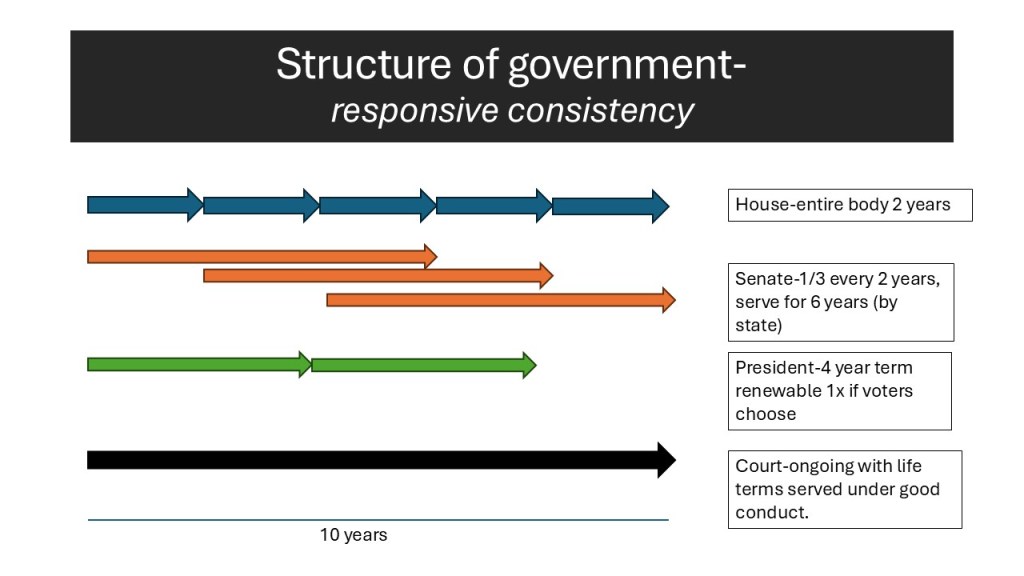

The overall idea here is for Congress to be responsive to the people by being elected every two years, but with the Senate staggered, there would be a constant government that wasn’t flighty or subject to the whims of popular culture. In addition, the Senate was the States’ representative house, like the Confederation while the House was responsive to the people directly. The Executive originally served as long as the people would continue to vote him in. Washington established a precedent by stepping down after two terms, signifying neither he nor anyone else would become a king. Every president followed his lead until FDR. As a result of FDR’s four terms, Congress passed the 22nd Amendment limiting his time to two terms. (A person who serves more than 2 years of his predecessor’s term can only serve one more.) Lastly, judges would serve a lifetime appointment. The staggered and unpredictable turnover of justices was intended to put them above the political fray.

If a new government was going to represent the people, it needed to be ratified by the people. Using existing members of Congress to meet state by state would be identical to having Congress vote and would result in rejection. What happened was a state-by-state campaign to elect representatives that committed ahead of time in favor of or against the Constitution. There were a few who promised to be open and persuadable, but most committed before the state convention began. The Federalist Papers originally appeared as a series of opinion articles in papers in New York City. They quickly became important documents for other states and were widely distributed. In response to the essays those against the Constitution made efforts to persuade the public to reject the new government. The essays in favor of ratification were eventually combined in a single place and given their name. No concerted effort has been made to consolidate the disparate efforts by those opposed.

I started this two-part series to step back and look at the founding ideas of our government. Over the two hundred thirty-six years since its adoption there have been many clarifications and changes. Some of those changes have been by amendment or legislation. Others are the result of decisions handed down by SCOTUS. It is fidelity to the ideas expressed in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution that make the US what it is. It is not based on a preset geography, ethnicity, or fidelity to a monarch. Our constitution was built to adapt to its times. The founders knew they couldn’t forsee the future. They built a document that is malleable. At its core, the government stands on the two pillars of consent of the governed and the rule of law.

Here are two images of the leaders from different countries accepting executive responsibility. On the left is Washington putting his hand on a bible and swearing an oath (by God) to protect and defend the Constitution. On the left is Napoleon Bonaparte taking the crown from the hands of the cardinal and placing it on his own head, signifying, like King Louis XIV, “I am the state.”