It was the gold. In the west it was often the gold. In the middle of the nineteenth century, it was the California gold and after that the Comstock gold. It was also the fertile fields of Oregon, gold of the nonmineral type. Correspondence in the days before electronics was either by word of mouth or mail. The need for mail came in two areas, letters home to people east of St. Louis, and commerce. Money and credit that connected the raw material of the west to the factories and commerce in the east. Six months for mail was too long.

It took Six months for mail arrive on a packet or ship that took the route around the horn of South America. Delivery time could be shorted by sailing to the eastern side of Panama and transloading freight and passengers across the isthmus to the Pacific side and then to San Francisco, but the mosquitos that caused yellow fever and malaria along with the heat took lives. What was really needed was a fast land route across the prairie and the Rockies.

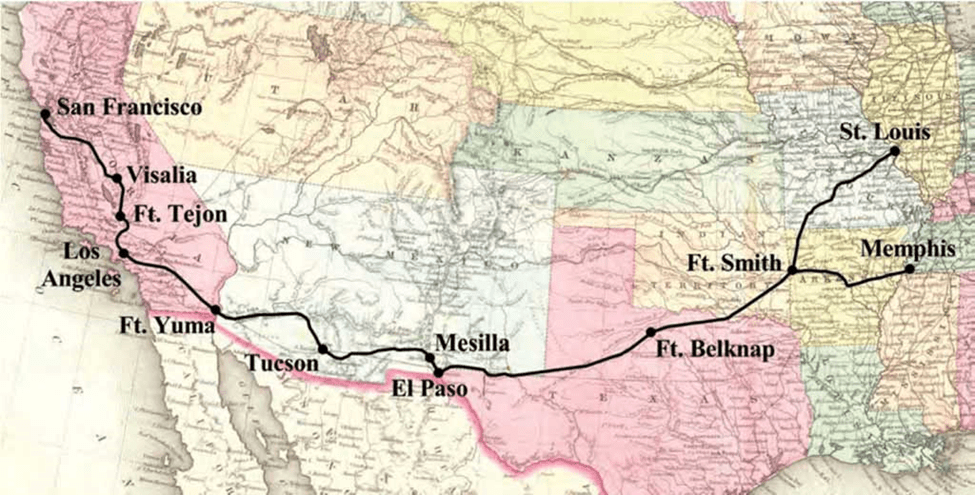

The Butterfield Overland Mail Company was the first government contractor to deliver mail twice a week beginning in 1857. The six-year contract followed a southern route that started in St. Louis, proceeded to Little Rock, Arkansas through Texas and Yuma, Arizona and eventually to Los Angeles where it then proceeded north to San Francisco. The $600,000 contract resulted in new and improved roads along with 139 new bridges along the way, according to Life on the Pony Express by Diane Yancey. The route was anything but easy as Shoshone, Apache, and Comanche tribes attacked the stage line along the way and the weather varied from cold and snowy in the winter to summer heat which according to one passenger was “as close to hell as (I) ever wished to be”.

A central route through the middle of the country using Salt Lake City as a pass-through point was highly desired. It would use the route followed by so many emigrants who ended up on the west coast. The call for mail service must have been loud and constant because in 1860, William H. Russell decided to establish an express service for mail independent of the US Postal service or Congressional financial backing. The Pony Express was almost immediately famous and has remained significant in the annals of the West.

The Pony Express was a short-lived affair lasting only 18 months from April 1860-October 1861. One reason for its brief time period was because the Pony never did receive a government contract to deliver the mail. An example of gumption, bravery, and success, the Pony Express lives in the memory of America as an example of Yankee ingenuity and a can-do spirit. The young riders driving through all kinds of weather to deliver the mail could be the ideal poster for the US Postal Services motto “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds” even if they were closer to UPS than the postal service.

It was young riders who made it happen as evidenced by a poster advertising the position:

Wanted-young skinny, wiry fellows not over eighteen. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred.

With a little imagination, the route can still be seen near Dayton, Nevada. Driving today on U.S. 50 from Carson City to the Utah border, a road that is parallel to the old route, in an air conditioned or heated car or truck it is easy to forget that in an era limited to dirt roads or trails, horses, and the raw environment, the most natural route followed water. The Carson River, flowing east from the Sierra Nevada passes through Carson City and Dayton, Nevada. The path made by the river was a thoroughfare for the Paiute people before the westward emigrants came to settle in the area. The crisis created by the intersection of the two cultures and creation of Fort Churchill will be the subject of another post. The Pony Express, Butterfield Overland stages, and eventually the railroad all used the same route along the river. In the twentieth century, U.S. 50 would be build along the same route, only a couple of miles to the north.

I went in search of the Stage and Pony Express route in the late summer. Much to my surprise, a section is still in use and has a few historical artifacts to mark the importance of the route to westward expansion.

A good route never goes out of fashion and today this section of the old Pony Express is mostly a dirt road. Along the sides of this very well-maintained road are signs of the reason the Pony Express didn’t last. First and foremost, are the telephone wires and poles. In the Pony’s day it was the telegraph not the yet-to-be-invented telephone that shortened communication times. The ability to communicate by wire in seconds made the ten day promise of the Express outdated. In the parlance of today, the mail service was disrupted.

The telegraph was largely laid by the railroad as part of the federal contract awarding the routes to the west. It is no surprise that the railroad is still a strong presence along the route. Another major presence is agriculture in the form of grass crops and range land. Both the telephone and train remain a strong presence along the route.

A rusted sign looking west over the desert stands as a reminder of the pressure exerted by the emigrants who followed the route to California. They came by the thousands, at first for the gold fields and then later for the rich agricultural fields in California’s Central Valley where the first major crops to be grown and sent east to feed the growing cities of immigrants fueling the industrial engine of the late 19th century were grain products like wheat, rice and other grassland staples. As an example of ambition, heroism, and expansion in the American west the Pony Express captures our attention today as it did in its own day